Model predictions could pave the way to new treatments

A new supercomputer-based brain simulation shows that motor tics in Tourette syndrome may arise from interactions between multiple areas of the brain, rather than a single malfunctioning area, according to a study published in PLOS Computational Biology.

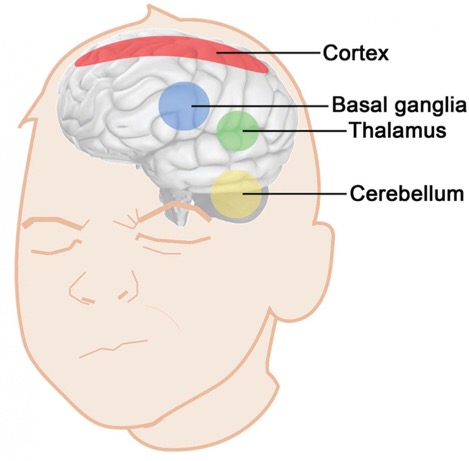

Tourette syndrome causes people to have involuntary motor tics, such as eye blinking, sniffing, or clapping. Traditionally, such tics were associated with dysfunction of a brain region known as the basal ganglia, but recent studies of rat, monkey, and human brains suggest that the cerebellum, thalamus, and cortex may be involved, too.

Based on this recent evidence, Daniele Caligiore of the National Research Council, Italy, and colleagues developed a supercomputer simulation of brain activity that underlies motor tics in Tourette syndrome. This model reproduces neural activity that was associated with tics in a recent study of the monkey brain, which showed that tics might also involve signaling between the cortex, basal ganglia, and cerebellum.

By tweaking the model to accurately reproduce the results of the monkey study, the researchers were able to use it to better understand how the brain might generate tics. The model suggests that abnormal dopamine activity in the basal ganglia works in tandem with activity in the thalamo-cortical system to trigger a tic. Meanwhile, the model suggests, the basal ganglia-cerebellum link discovered in the monkey study may allow the cerebellum to influence tic production, as well.

"This model represents the first computational attempt to study the role of the recently discovered basal ganglia-cerebellar anatomical links," Caligiore says.

The researchers also found that the model can be used to predict the number of tics generated when there are dysfunctions in the neural circuits that connect the basal ganglia, thalamus, cortex, and cerebellum. These predictions could aid identification of new brain regions that could serve as targets of new treatments to reduce motor tics.

Caligiore says the model represents a first step toward building "virtual patients" to test potential therapies via supercomputer simulations. "These simulations can be performed with little costs and no ethical implications and could suggest promising therapeutic interventions to be tested in focused investigations with real patients," he says.