THE LATEST

Brazilian supercomputer simulations produce discovery to enhance enzyme that degrades plastic

Brazilians participate in international project to boost capacity of PETase of breaking down polyethylene terephthalate (PET), used in bottles and responsible for producing millions of tons of waste

Since it was discovered, the enzyme known as PETase has been drawing a great deal of scientific interest for its capacity of digesting PET (polyethylene terephthalate).

A polymer used mainly to manufacture drink bottles (but also clothing, carpets, and other objects), PET is appreciated by the industry for the same reason that makes PET a threat for the environment: its resistance to degradation. Bottles and other objects made of PET (polyethylene terephthalate) take at least 800 years to biodegrade in landfills or the sea. Between 4.8 billion and 12.7 billion kilograms of plastic are dumped in the oceans every year.

{module In-article}

A research with results published (http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2018/04/16/1718804115) recently in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS) showed how an international team of collaborators managed to boost PETase's capacity to break down plastic.

"In our research project, we characterized the three-dimensional structure of the enzyme that can digest this plastic, engineered it to boost its degradation capacity, and demonstrated that it also acts on polyethylene-2,5-furandicarboxylate (PEF), a PET substitute made from renewable raw materials," said Rodrigo Leandro Silveira (http://www.bv.fapesp.br/en/pesquisador/85580/rodrigo-leandro-silveira), a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Campinas's Chemistry Institute (IQ-UNICAMP) supported by the São Paulo Research Foundation - FAPESP, who co-signed the article.

Also listed as co-authors are scientists from University of Portsmouth (UK) and from United States' National Renewable Energy Laboratory who collaborated in the research, as well as Silveira's supervisor Munir Salomão Skaf (http://www.bv.fapesp.br/en/pesquisador/2269/munir-salomao-skaf). A Full Professor at UNICAMP and also its Pro-Rector for Research, Skaf runs the Center for Engineering and Computational Sciences (CCES http://cepid.fapesp.br/en/centro/13) - one of FAPESP's Research, Innovation and Dissemination Centers (RIDCs http://cepid.fapesp.br/en/home) - which also provided funding for the research.

A bacteria which survives metabolizing PET

Interest in PETase arose in 2016, when a group of Japanese researchers led by Shosuke Yoshida identified a new species of bacterium, Ideonella sakaiensis, that can "feed" on PET by using it as a source of carbon and energy. The bacterium remains the only known organism with this ability. It literally grows on PET.

"Besides identifying I. sakaiensis, the Japanese scientists discovered that it produces two enzymes and secretes them into the environment," Silveira explained. "One of the enzymes secreted is precisely PETase. Because it has a certain degree of crystallinity, PET is a polymer that's very hard to break down. But PETase attacks it and breaks it down into small units of mono(2-hydroxyethyl) terephthalic acid, or MHET. The units of MHET are then converted into terephthalic acid and absorbed and metabolized by the bacterium."

I. Sakaiensisis the only living being known for using not biomolecules, but rather a synthetic molecule manufactured by humans in order to survive. This means the bacterium is the result of a very recent evolutionary process that has unfolded over the last few decades. The bacterium has adapted to a polymer that was developed in the early 1940s and only began to be used on an industrial scale in the 1970s. PETase is the key to understanding how.

"PETase does the hardest part, which is breaking down the crystal structure and depolymerizing PET into MHET," said the FAPESP-funded researcher. "The work done by the second enzyme, which converts the MHET into terephthalic acid, is much simpler, because its substrate consists of monomers that the enzyme can access easily because they're dispersed in the reaction medium. For this reason, research has focused on PETase."

Modified enzyme binds better with polymer

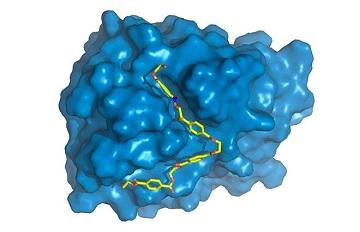

The next step was to study PETase in detail, and this is the contribution made by the new research project. "We focused on finding out what gives PETase the capacity to do something other enzymes can't do very efficiently. We began by characterizing the 3D structure of this protein," Silveira explained.

"Obtaining the 3D structure means discovering the x, y and z coordinates of each of the thousands of atoms that comprise the macromolecule. Our British colleagues did this using a well-known and widely used technique called X-ray diffraction available at a laboratory very similar to Sirius (http://www.lnls.cnpem.br/sirius-en), now under construction in Campinas."

Once they had obtained the 3D structure, the researchers began comparing PETase with related proteins. The closest relative is a cutinase of the bacterium Thermobifida fusca that degrades cutin, a sort of natural varnish found on the leaves of plants. Certain pathogenic microorganisms use cutinase to break down the cutin barrier and appropriate nutrients in leaves.

"We found some specific differences in PETase compared with cutinase in the region of the enzyme where the chemical reactions occur, known as the active site. PETase has a more open active site, for example," Silveira said. "We studied the enzyme's molecular movements through supercomputer simulations, the part to which I contributed most. While crystal structure, obtained by X-ray diffraction, provided static information, simulations gave us dynamic information and enable us to discover the specific role of each amino acid in the PET degradation process."

The physics of the molecule's movements results from electrostatic attraction and repulsion of a great many atoms and from temperature. Supercomputer simulations enabled the researchers to understand more completely how PETase binds and interacts with PET.

"We discovered that PETase and cutinase have two different amino acids at the active site. We then used molecular biology procedures to produce mutations in PETase with the aim of converting it into cutinase," Silveira said.

"If we could do that, we'd show why PETase is PETase. In other words, we'd find out which components gave it this unique property of degrading PET. However, to our surprise, when we tried to suppress this particular activity of PETase - by trying to convert PETase into cutinase - we produced an even more active PETase. We tried to reduce its activity, and instead we boosted it."

More supercomputer simulations were required to understand why the mutant PETase was better than the original PETase. Modeling and simulations clearly showed that the alterations produced in the original PETase facilitated the enzyme's binding to the substrate.

This binding depends both on geometry, with two molecules fitting together like key and keyhole, and on the thermodynamic factors involved in the interactions among the various components of the enzyme and the polymer. The elegant way to describe this is that the modified PETase has "greater affinity" for the substrate.

In terms of a future practical application, of obtaining an ingredient that can digest tons of plastic waste, the study was a great success, but why PETase is PETase remains a mystery.