Germany's AWI sheds light on Arctic zooplankton migration in the face of climate change

Due to intensifying sea ice melting in the Arctic, sunlight is now penetrating deeper and deeper into the ocean. Since marine zooplankton respond to the available light, this is also changing their behavior – especially how the tiny organisms rise and fall within the water column. As an international team of researchers led by the Alfred Wegener Institute has now shown, in the future this could lead to more frequent food shortages for the zooplankton, and to adverse effects for larger species including seals and whales. AWI is the biggest institution for polar and ocean research and science in Germany.

In response to anthropogenic climate change, the extent and thickness of the Arctic sea ice are declining; the mean sea ice extent is currently decreasing at a rate of 13 percent per decade. As early as 2030 – as the latest studies and supercomputer simulations indicate – the North Pole could see its first ice-free summer. As a result, the physical conditions for organisms in the Arctic Ocean are changing just as visibly. For example, due to less and thinner sea ice, sunlight can penetrate much farther below the surface. As a result, under certain conditions, the primary production – i.e., the growth – of microalgae in the water and ice can increase substantially. How these changing light conditions are affecting higher trophic levels in the food chain – like zooplankton, which feed in part on microalgae – remains poorly understood. In this regard, an international team of researchers led by Dr Hauke Flores from the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI) has now gained valuable insights.

According to Flores: “Every day, the largest-scale mass movement of organisms on our planet takes place in the ocean – the daily migration of the zooplankton, which include tiny copepods and krill. At night, the zooplankton rises near the water’s surface to feed. When the day comes, they migrate back to the deep, protecting them from predators. Although the individual organisms are minuscule, taken together this constitutes a tremendous daily vertical motion of biomass within the water column. But in the polar regions, the migration is different – it’s seasonal; in other words, the zooplankton follow a seasonal cycle. During the months-long brightness of the Polar Day in summer, they remain in the deep; during the months-long darkness of the Polar Night in winter, part of the zooplankton rise and remain in the near-surface water just below the ice.”

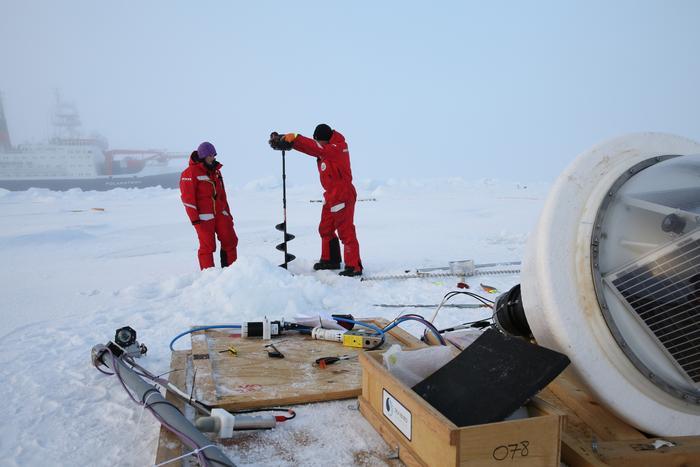

Both the daily migration at lower latitudes and the seasonal migration in the polar regions are predominantly dictated by sunlight. The tiny organisms usually prefer twilight conditions. They like to stay below a certain light intensity (critical irradiance), which is usually quite low and lies well into the twilight range. When the intensity of sunlight changes in a day or the seasons, the zooplankton go where they can find their preferred light conditions, which ultimately means they rise or sink in the water column. “Particularly when it comes to the topmost 20 meters of the water column, just below the sea ice, there was no available data on the zooplankton,” Flores explains. “But it’s precisely this hard-to-reach area that’s most interesting because it’s in and just below the ice where the microalgae that the zooplankton feed on grows.” To take readings there, the team designed and built an autonomous biophysical observatory, which they moored below the ice at the end of the MOSAiC expedition with the AWI research icebreaker Polarstern in September 2020. Here – far from any light pollution due to human activities – the system was able to continually measure the light intensity below the ice and the zooplankton’s movements.

“Based on our readings, we identified an extremely low critical irradiance for the zooplankton: 0.00024 watts per square meter,” says the AWI researcher. “We then fed this parameter into our supercomputer models for simulating the sea-ice system. This allowed us to project, for a range of climate scenarios, how the depth of this irradiance level would change by the middle of this century if the sea ice grew thinner and thinner due to climate change.” What the experts found: Due to the steadily declining ice thickness, the critical irradiance level would drop to greater depths earlier and earlier in the year and wouldn’t return to the surface layer until later and later in the year. Since the zooplankton remains in waters below this critical level, their movements would mirror this change. Accordingly, in these future scenarios, they remain at greater depths longer and longer, while their time near the surface below the ice in winter grows shorter and shorter.

“In warmer future climates, the ice will form later in the autumn, resulting in reduced ice-algae production,” Flores explains. “This, in combination with their delayed rise to the surface, could lead to more frequent food shortages for the zooplankton in winter. At the same time, if the zooplankton rises earlier in the spring, it could endanger the larvae of ecologically important zooplankton species living at deeper levels, more of which could then be eaten by the adults.”

“Altogether, our study points to a previously overlooked mechanism that could further reduce Arctic zooplankton’s chances of survival shortly,” says Flores. “If that comes to pass, it will have fatal consequences for the entire ecosystem, including seals, whales, and polar bears. But our simulations also show that the impact on vertical migration will be much less pronounced if the 1.5-degree target can be reached than if greenhouse gas emissions rise unchecked. Accordingly, every tenth of a degree of anthropogenic warming that can be avoided is critical for the Arctic ecosystem.”

The study conducted by Germany's AWI shows that climate change is having a significant effect on the seasonal vertical migration of zooplankton in the Arctic. This is a worrying trend, as the zooplankton are an important part of the food web and play a critical role in the health of the Arctic ecosystem. As temperatures continue to rise, the effects of climate change on the zooplankton will likely become even more pronounced, leading to further disruption of the Arctic food web and potentially catastrophic consequences for the Arctic environment.

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?