ACADEMIA

Space shuttle data leads to better model for solar power production in California

The space shuttle program may have ended, but data the space craft collected over the past three decades are still helping advance science. Researchers at the Jacobs School of Engineering at UC San Diego recently used measurements from NASA's Shuttle Radar Topography Mission to predict how changes in elevation, such as hills and valleys, and the shadows they create, impact power output in California's solar grid.

Current large-scale models used to calculate solar power output do not take elevation into account. The California Public Utilities Commission asked Jan Kleissl, a professor of environmental engineering at the Jacobs School of Engineering at UC San Diego, and postdoctoral researcher Juan Luis Bosch, from the department of mechanical and aerospace engineering, to build a model that does.

This is the first time this kind of model will be made available publicly on such a large scale, including all of Southern California, as well as the San Francisco Bay Area. It took the Triton Supercomputer at the San Diego Supercomputer Center here at UCSD 60,000 processor hours to run calculations for the model. Utility companies and homeowners can use the model to get a more realistic picture of the solar power output they can typically expect to produce. This is an especially important tool for utilities, because it gives them a better idea of how much revenue they can actually generate, Kleissl said.

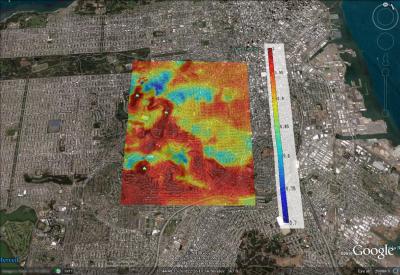

Changes in elevation can have a significant impact on solar power output. The longer it takes for the sun to rise above the local horizon in the morning and the earlier it sets in the evening, the more solar fuel is lost. Solar days are longest on top of tall mountains. They are shortest in steep valleys oriented north-south, where it can take more than an hour longer for the sun to appear in the east.For example, on clear winter days in San Francisco's Twin Peaks neighborhood, in the areas at the foot of the steepest hills, solar days are up to 30 percent shorter than on flat terrain. A solar power plant in that area would produce 12 percent less energy on those days than if it was located on a plain or other flat landscape. But in summertime, the days are much longer and the sun is brighter, so the total production shortfall would be only 1 to 2 percent over the course of a whole year.

"Solar resource models have become very accurate," said Kleissl. "Now we are refining them down to the last few percentage points."

Bosch, the postdoctoral researcher, used elevation data obtained on a near-global scale by astronauts aboard the space shuttle Endeavour during an 11-day mission in February 2000. The data were later compiled into a high-resolution digital topographic database of most of planet Earth. Bosch and Kleissl focused on the areas of California where most solar power plants are located and where elevation is an issue, namely the San Francisco Bay Area and Southern California, including San Diego, Imperial, Riverside, Orange and Los Angeles counties.

One caveat for the method developed by Kleissl and Bosch is that it provides only baseline information in urban areas. Trees, poles and other rooftop structures, such as chimneys, can cause more power losses. In that case, the best method to estimate power shortfalls is to use a fisheye camera to visualize the local horizon, a device that any qualified installer of solar panels would have on hand.