ACADEMIA

Swedish scientists reveal Jupiter's unknown journey

The giant planet Jupiter was formed four times further away from the sun than its current orbit. It took only 700,000 years for the giant to move inward in the solar system. The scientists have found the proof of this powerful journey thanks to a number of asteroids around Jupiter.

It is known that gas giants around other stars are often very close to their sun. According to current theory, these gas planets have been formed far away and then migrated to a path near the star.

Now researchers from, among others, Lund University have taken advantage of advanced supercomputer calculations to put their finger on the gas giant Jupiter's journey through our own solar system for about 4.5 billion years ago. Jupiter was then fairly newly formed, like the other planets in the solar system. The planets were gradually built up by the cosmic dust, which revolved around our young sun in a slab of gas and dust. At that time, Jupiter was no bigger than our own planet.  {module In-article}

{module In-article}

In the current research study, it has been calculated that Jupiter was formed four times further away from the sun than what its current position testifies to.

- This is the first time we have evidence that Jupiter was formed far from the sun and then migrated to its current path, says Simona Pirani, PhD student in astronomy at Lund University.

Simona Pirani is the lead author of the scientific article on Jupiter's migration. The current study has also made calculations on the gas giant Saturn and the ice cream giants Uranus and Neptune. The researchers note that even these giant planets must have migrated in the same way as Jupiter.

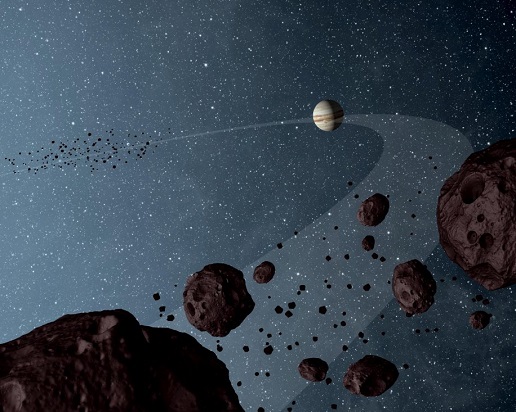

"The evidence for the migration can be found in the Trojan asteroids that revolve near Jupiter," says Simona Pirani.

The Trojan asteroids adjacent to Jupiter consist of two groups of thousands of asteroids that lie in front of and behind Jupiter respectively. They orbit the same orbit as the planet. There are about 50 percent more Trojans in front of Jupiter than behind, and this is the asymmetry that became the key for scientists to understand Jupiter's migration.

- This asymmetry has been a mystery in the solar system, says Anders Johansen, professor of astronomy at Lund University.

The research world has so far been unable to explain why the two asteroid groups are different in size. But now, Simona Pirani and Anders Johansen, together with some colleagues, have found the cause by recreating the sequence of events for Jupiter's formation and for how the planet gradually captured its Trojan asteroids.

Thanks to extensive supercomputer simulations, researchers have calculated that the current asymmetry may only have occurred if Jupiter was formed four times further away in the solar system and then migrated to its present location. During the journey to the sun, Jupiter's own gravity captured more trojans in front of them than behind them.

According to the researchers' calculations, Jupiter's migration should have been around 700,000 years, for a period of about 2-3 million years after the celestial body began its life as an isasteroid far from the sun. The journey inward into the solar system took place in a spiral-shaped movement where Jupiter continued to circle around the sun but in an increasingly narrow path. The underlying reason for the migration itself has to do with gravity forces from the surrounding gas in the solar system.

The supercomputer simulations show that the Trojan asteroids were captured when Jupiter was a young planet without a gas body, which means that these asteroids most likely consist of similar building blocks that formed Jupiter's interior. In 2021, NASA's space probe, Lucy, will be postponed to revolve around six of Jupiter's Trojan asteroids and study them.

"We can learn a lot about Jupiter's core and education by studying the Trojans," said Anders Johansen.

The current study has now been published in the scientific journal Astronomy & Astrophysics . The research is funded by the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation.