Being in-between living and non-living, viruses are, in general, strange. Among viruses, multipartite viruses are among the most peculiar—their genome is not packed into one, but many, particles. Multipartite viruses primarily infect plants rather than animals. A recent paper by researchers from the Tokyo Institute of Technology (Tokyo Tech) uses mathematical and computational models to explain this observation.

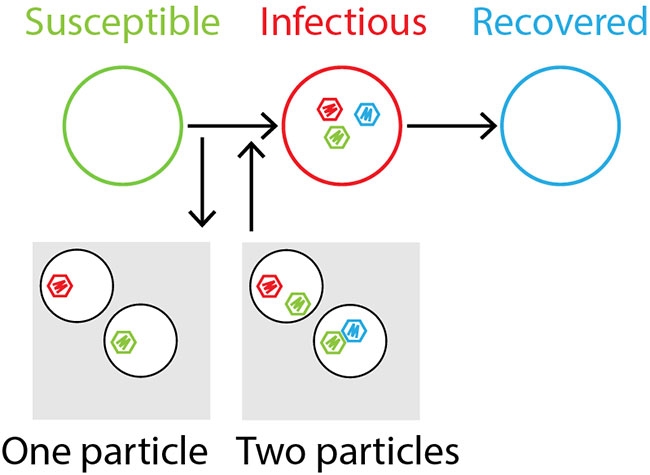

Multipartite viruses have a strange lifestyle. Their genome is split up into different viral particles that, in principle, propagate independently. Completing the replication cycle, however, requires the full genome such that persistent infection of a host requires the concurrent presence of all types of particles (see Fig. 1). The origin of multipartite viruses is an evolutionary puzzle. Apart from why they can have such a costly lifestyle, the most peculiar thing about them is that almost all known multipartite viruses infect either plants or fungi—very few viral species infect animals.

So far, most theoretical research has been trying focusing on explaining how it is viable to have the genome split into different particles. This paper provides a theoretical explanation of why multipartite viruses primarily infect plants.  {module In-article}

{module In-article}

There have been great efforts to understand the mechanisms that give multipartite viruses an advantage that can compensate for their peculiar and costly lifestyle, and this is not yet a solved problem. Also, our understanding of why most multipartite viruses infect only plants is limited. In a recent work, published in Physical Review Letters, Petter Holme of the World Research Hub Initiative, Tokyo Tech, and colleagues from China and the USA, have explained why multipartite viruses primarily infect plants. In their work, the authors formulated a minimal network-epidemiological model.

They used mathematical models and supercomputer simulations to show that multipartite viruses colonize a structured population (representing the interaction patterns among plants) with less resistance, compared to a well-mixed population (representing the interaction patterns among animals). This is thus an explanation of why multipartite viruses infect plants rather than animals.

The researchers from Tokyo Tech continue to investigate the epidemiology of different types of infectious diseases by theoretical methods. At the moment, they are interested in the more common disease spreading scenarios such as how influenza spreads in cities and how that could be mitigated.

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?