Associate professor Mazhar Ali and his research group at TU Delft, the oldest and largest Dutch public technical university, located in Delft, Netherlands, have discovered one-way superconductivity without magnetic fields, something that was thought to be impossible ever since its discovery in 1911 – up till now. The discovery makes use of 2D quantum materials and paves the way towards superconducting computing. Superconductors can make electronics hundreds of times faster, all with zero energy loss. Ali: “If the 20th century was the century of semi-conductors, the 21st can become the century of the superconductor.”  During the 20th century many scientists, including Nobel Prize winners, have puzzled over the nature of superconductivity, which was discovered by Dutch physicist Kamerlingh Onnes in 1911 (read more about this in the frame below). In superconductors, a current goes through a wire without any resistance, which means inhibiting this current or even blocking it is hardly possible – let alone getting the current to flow only one way and not the other. That Ali’s group managed to make superconducting one-directional – necessary for computing – is remarkable: one can compare it to inventing a special type of ice that gives you zero friction when skating one way, but insurmountable friction the other way.

During the 20th century many scientists, including Nobel Prize winners, have puzzled over the nature of superconductivity, which was discovered by Dutch physicist Kamerlingh Onnes in 1911 (read more about this in the frame below). In superconductors, a current goes through a wire without any resistance, which means inhibiting this current or even blocking it is hardly possible – let alone getting the current to flow only one way and not the other. That Ali’s group managed to make superconducting one-directional – necessary for computing – is remarkable: one can compare it to inventing a special type of ice that gives you zero friction when skating one way, but insurmountable friction the other way.

Superconductor: super-fast, super-green

The advantages of applying superconductors to electronics are twofold. Superconductors can make electronics hundreds of times faster, and implementing superconductors into our daily lives would make IT much greener: if you were to spin a superconducting wire from here to the moon, it would transport the energy without any loss. For instance, the use of superconductors instead of regular semi-conductors might save up to 10% of all western energy reserves according to NWO.

The (Im)possibility of applying superconducting

In the 20th century and beyond, no one could tackle the barrier of making superconducting electrons go in just one direction, which is a fundamental property needed for computing and other modern electronics (consider for example diodes that go one way as well). In normal conduction the electrons fly around as separate particles; in superconductors, they move in pairs of twos, without any loss of electrical energy. In the 70s, scientists at IBM tried out the idea of superconducting computing but had to stop their efforts: in their papers on the subject, IBM mentions that without non-reciprocal superconductivity, a computer running on superconductors is impossible.

Interview with Mazhar Ali

Q: Why, when one-way direction works with normal semi-conduction, has one-way superconductivity never worked before?

Mazhar Ali: “Electrical conduction in semiconductors, like Si, can be one-way because of a fixed internal electric dipole, so a net built-in potential they can have. The textbook example is the famous "pn junction"; where we slap together two semiconductors: one has extra electrons (-) and the other has extra holes (+). The separation of charge makes a net built-in potential that an electron flying through the system will feel. This breaks the symmetry and can result in "one-way" properties because forward vs backward, for example, are no longer the same. There is a difference in going in the same direction as the dipole vs going against it; similar to if you were swimming with the river or swimming up the river.”

“Superconductors never had an analog of this one-directional idea without magnetic field; since they are more related to metals (i.e. conductors, as the name says) than semiconductors, which always conduct in both directions and don't have any built-in potential. Similarly, Josephson Junctions (JJs), which are sandwiches of two superconductors with non-superconducting, classical barrier materials in-between the superconductors, also haven't had any particular symmetry-breaking mechanism that resulted in a difference between "forward" and "backward".

Q: How did you manage to do what first seemed impossible?

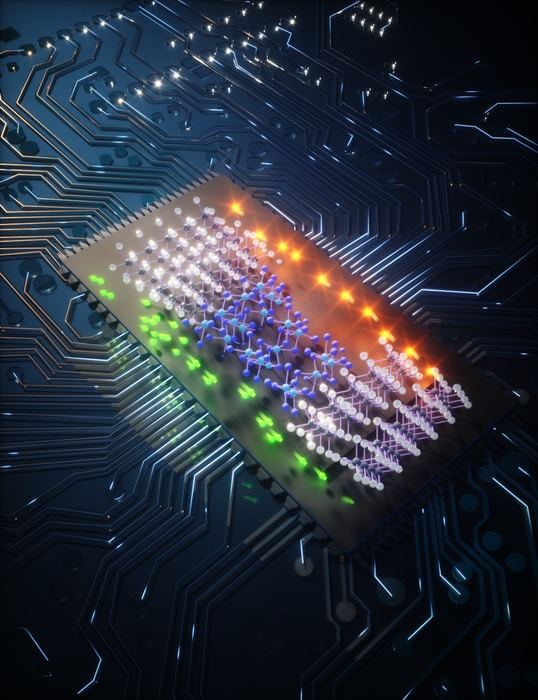

Ali: “It was really the result of one of my group's fundamental research directions. In what we call "Quantum Material Josephson Junctions" (QMJJs), we replace the classical barrier material in JJs with a quantum material barrier, where the quantum material's intrinsic properties can modulate the coupling between the two superconductors in novel ways. The Josephson Diode was an example of this: we used the quantum material Nb3Br8, which is a 2D material like graphene that has been theorized to host a net electric dipole, as our quantum material barrier of choice and placed it between two superconductors.”

“We were able to peel off just a couple atomic layers of this Nb3Br8 and make a very, very thin sandwich - just a few atomic layers thick - which was needed for making the Josephson diode, and was not possible with normal 3D materials. Nb3Br8 is part of a group of new quantum materials being developed by our collaborators, Professor Tyrel McQueen and his group at Johns Hopkins University in the USA, and was a key piece in us realizing the Josephson diode for the first time.”

Q: What does this discovery mean in terms of impact and applications?

Ali: “Many technologies are based on old versions of JJ superconductors, for example, MRI technology. Also, quantum computing today is based on Josephson Junctions. Technology that was previously only possible using semi-conductors can now potentially be made with superconductors using this building block. This includes faster computers, as in computers with up to terahertz speed, which is 300 to 400 times faster than the computers we are now using. This will influence all sorts of societal and technological applications. If the 20th century was the century of semi-conductors, the 21st can become the century of the superconductor.”

“The first research direction we have to tackle for commercial application is raising the operating temperature. Here we used a very simple superconductor that limited the operating temperature. Now we want to work with the known so-called "High Tc Superconductors", and see whether we can operate Josephson diodes at temperatures above 77 K since this will allow for liquid nitrogen cooling. The second thing to tackle is the scaling of production. While it’s great that we proved this works in nanodevices, we only made a handful. The next step will be to investigate how to scale production to millions of Josephson diodes on a chip.”

Q: How sure are you of your case?

Ali: “There are several steps which all scientists need to take to maintain scientific rigor. The first is to make sure their results are repeatable. In this case, we made many devices, from scratch, with different batches of materials, and found the same properties every time, even when measured on different machines in different countries by different people. This told us that the Josephson diode result was coming from our combination of materials and not some spurious result of dirt, geometry, machine or user error or interpretation.”

“We also carried out "smoking gun" experiments that dramatically narrow the possibility for interpretation. In this case, to be sure that we had a superconducting diode effect we actually tried "switching" the diode; as in we applied the same magnitude of current in both forward and reverse directions and showed that we actually measured no resistance (superconductivity) in one direction and real resistance (normal conductivity) in the other direction.”

“We also measured this effect while applying magnetic fields of different magnitudes and showed that the effect was clearly present at 0 applied field and gets killed by an applied field. This is also a smoking gun for our claim of having a superconducting diode effect at a zero-applied field, a very important point for technological applications. This is because magnetic fields at the nanometer scale are very difficult to control and limit, so for practical applications, it is generally desired to operate without requiring local magnetic fields.”

Q: Is it realistic for ordinary computers (or even the supercomputers of KNMI and IBM) to make use of superconducting?

Ali: “Yes it is! Not for people at home, but for server farms or supercomputers, it would be smart to implement this. Centralized computation is really how the world works nowadays. Any and all intensive computation is done at centralized facilities where localization adds huge benefits in terms of power management, heat management, etc. The existing infrastructure could be adapted without too much cost to work with Josephson diode-based electronics. There is a very real chance, if the challenges discussed in the other question are overcome, that this will revolutionize centralized and supercomputing!”

TU Delft discovers the one-way superconductor, thought to be impossible

Like

Like

Happy

Love

Angry

Wow

Sad

Comments (0)

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?