Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) senior scientist of physical oceanography, Dr. Young-Oh Kwon, and WHOI adjunct scientist, Dr. Claude Frankignoul, have received a new research grant from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Modeling, Analysis, Predictions and Projections (MAPP) Program, funding their research project focusing on western boundary ocean currents and their correspondence with the atmosphere concerning the modern-day climate.

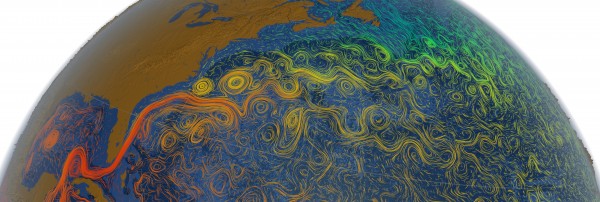

Western boundary currents (WBCs), such as the Kuroshio-Oyashio Extension in the North Pacific Ocean and the Gulf Stream in the North Atlantic Ocean, are the regions of largest ocean variability and intense air-sea interaction. This WBC variability generates strong ocean-to-atmosphere heat transfer, resulting in warming that can impact large-scale atmospheric circulation and heat transport toward the poles in both the ocean and atmosphere.

The project suggests that this WBC behavior and its associated air-sea interaction play fundamental roles in regulating our climate, as well as have a significant impact on extreme weather, coastal ecosystem, and sea level. However, their representation in climate models needs to be improved. This study looks to investigate the nature and impacts of the WBC variability in state-of-the-art climate models based on a set of model diagnostics. Kwon and his team will develop the diagnostics for this study based on various observational datasets. Then, they will be used to determine the differences between observations and the climate model simulations (or model biases) at standard and higher resolutions.

According to Kwon, the findings would lead to a system of quantifying the oceanic and atmospheric variability in the WBCs resulting from air-sea interactions, and an improved understanding of the links between the model biases in simulating WBCs and the simulated large-scale atmospheric and oceanic circulations.

“The recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report was very clear: climate change is widespread, rapid, and intensifying, hence the research to improve our physical understanding of the climate system and model biases are needed more than ever,” said Kwon.

“Our overall goals are to advance scientific understanding, monitoring, and prediction of climate and its impacts, enable effective decisions, especially since the improvement in the climate model processes related to the WBC variability and associated air-sea interaction has significant implications for the prediction of our climate and its impacts,” Kwon added.

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?