Space physicist Mark Conde had been seeing something curious in his atmospheric research data since the 1990s.

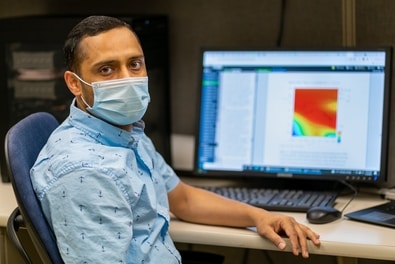

Three years ago, he realized the odd behavior of extreme upper-level wind was a real phenomenon and not a problem with instrumentation. He chose to hand the mystery to his research student, Rajan Itani, who is pursuing a doctorate in physics at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Itani confirmed that the cross-polar jet, a well-known wind in the upper atmosphere, sometimes inexplicably stops or is deflected or reversed when it reaches the region above Alaska. The finding upends previous understanding of the wind's behavior and has implications for spacecraft orbits, space debris avoidance, ionospheric storm modeling, and our understanding of the transport of air in the thermosphere. That portion of the atmosphere is far less dense, almost to a vacuum, compared to air at the Earth’s surface. And that means the occasional stalling of the cross-polar jet won’t be noticed on the surface or affect life here.

Itani’s paper on the topic, co-authored by Conde, was published in September by the Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics and included in the editor’s highlights in the American Geophysical Union magazine Eos.

Itani’s research at the UAF Geophysical Institute, with assistance from Conde and, conducted mostly with data from UAF's Poker Flat Research Range, focused only on the Alaska region. But, likely, the cross-polar jet would also stall elsewhere on the globe at high latitudes as the wind emerges from the polar cap around midnight.

Conde and Itani were studying the upper thermosphere, the region of the atmosphere above 90 miles altitude.

This cross-polar jet carries the thin air in this region over the North Pole from the Earth’s dayside to its nightside and delivers it toward the equator, where it dissipates. Sometimes, according to Itani’s research, the forces driving the wind aren’t strong enough to push it through the background atmosphere on the Earth’s night side.

“All of the computer models say that this wind spills out quite some distance toward the equator and then eventually slows and blends into the background flow, just like traffic merging onto a highway,” said Conde, who is a professor in the UAF Department of Physics. “There should be quite a strong flow extending far equatorward, but we find that it basically just hits a wall over Alaska on some occasions. It really should continue and spill out just like the models say.”

But what causes this stalling? That hasn’t been resolved yet. Itani’s paper does offer a correlation, however: A review of seven years of data shows a “strong influence” from solar activity. Thermospheric wind stalling is most likely to occur during solar minimum, the period of low disturbance on the sun’s surface.

Conde had seen the wind stalling in data at various times since the late 1990s when he began studying the impact of auroral displays on thermospheric winds above Alaska.

"Over the years as we've run multiple instruments and combined the data from those many instruments, I eventually just came to understand that what we were seeing was a real phenomenon,” he said.

Conde published a paper in 2018 that noted the thermospheric wind stalling; however, Itani’s paper expands on that work in more detail.

“Training the next generation of scientists is a major objective of the United States’ premier research institution, the National Science Foundation, which funded the work,” Conde said. “As a result, quite a bit of leading-edge research is done by graduate students. I am very pleased to see Rajan’s work in this area recognized by the American Geophysical Union.”

The mention in Eos was a career first for Itani. The magazine notes that fewer than 2% of papers receive such attention.

“I am delighted that our paper has been featured as an editor's highlight in Eos,” Itani said. “It is a proud moment in my career in space physics, as it marks my first paper being promoted. I am thankful to my adviser, Dr. Mark Conde, for suggesting the research topic and for his endless support and encouragement.”

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?