CLOUD

Study: CT scans could bolster forensic database to ID unidentified remains

A study from North Carolina State University finds that data from CT scans can be incorporated into a growing forensic database to help determine the ancestry and sex of unidentified remains. The finding may also have clinical applications for craniofacial surgeons.

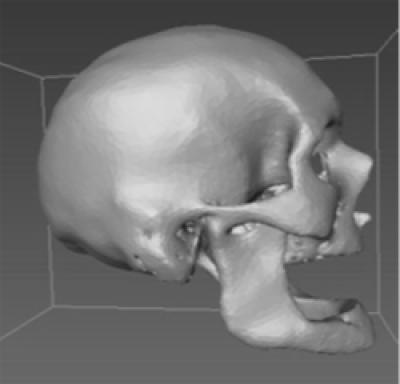

"As forensic anthropologists, we can map specific coordinates on a skull and use software that we developed – called 3D-ID – to compare those three-dimensional coordinates with a database of biological characteristics," says Dr. Ann Ross, a professor of anthropology at NC State and senior author of a paper describing the work. "That comparison can tell us the ancestry and sex of unidentified remains using only the skull – which is particularly valuable when dealing with incomplete skeletal remains."

However, the size of the 3D-ID database has been limited by the researchers' access to contemporary skulls that have clearly recorded demographic histories.

To develop a more robust database, Ross and her team launched a study to determine whether it was possible to get good skull coordinate data from living people by examining CT scans.

The University of Pennsylvania Museum's Morton Collection provided the NC State researchers with CT scans of 48 skulls. Researchers mapped the coordinates of the actual skulls manually using a digitizer, or electronic stylus. Then they compared the data from the CT scans with the data from the manual mapping of the skulls.

The researchers found that eight bilateral coordinates on the skull – those found on either side of the head – were consistent for both the CT scans and manual mapping.

"This will allow us to significantly expand the 3D-ID database," Ross says. "And these bilateral coordinates give important clues to ancestry, because they include cheekbones and other facial characteristics."

However, the five midline coordinates the researchers tested showed inconsistencies between the CT scans and manual mapping. Midline coordinates are those found along the center of the skull, such as the bridge of the nose.

"More research is needed to determine what causes these inconsistencies, and whether we'll be able to retrieve accurate midline data from CT scans," says Amanda Hale, a former master's student at NC State and lead author of the paper.

This research may also help craniofacial surgeons. "An improved understanding of the flaws in how CT scans map skull features could help surgeons more accurately map landmarks for reconstructive surgery," Hale says.

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?