ENGINEERING

ORNL demystifies forces at play in biofuel production

Researchers studying more effective ways to convert woody plant matter into biofuels at the Department of Energy's Oak Ridge National Laboratory have identified fundamental forces that change plant structures during pretreatment processes used in the production of bioenergy.

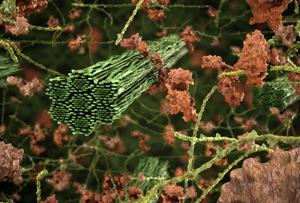

The research team, which published its results in Green Chemistry, set out to decipher the inner workings of plant cell walls during pretreatment, the most expensive stage of biofuel production. Pretreatment subjects plant material to extremely high temperature and pressure to break apart the protective gel of lignin and hemicellulose that surrounds sugary cellulose fibers.

“While pretreatments are used to make biomass more convertible, no pretreatment is perfect or complete,” said ORNL coauthor Brian Davison. “Whereas the pretreatment can improve biomass digestion, it can also make a portion of the biomass more difficult to convert. Our research provides insight into the mechanisms behind this ‘two steps forward, one step back’ process.”

The team’s integration of experimental techniques including neutron scattering and X-ray analysis with supercomputer simulations revealed unexpected findings about what happens to water molecules trapped between cellulose fibers.

“As the biomass heats up, the bundle of fibers actually dehydrates -- the water that’s in between the fibers gets pushed out,” said ORNL’s Paul Langan. “This is very counterintuitive because you are boiling something in water but simultaneously dehydrating it. It’s a really simple result, but it’s something no one expected.”

This process of dehydration causes the cellulose fibers to move closer together and become more crystalline, which makes them harder to break down.

In a second part of the study, the researchers analyzed the two polymers called lignin and hemicellulose that bond to form a tangled mesh around the cellulose bundles. According to the team’s experimental observations and simulations, the two polymers separate into different phases when heated during pretreatment.

“Lignin is hydrophobic so it repels water, and hemicellulose is hydrophilic, meaning it likes water,” Langan said. “Whenever you have a mixture of two polymers in water, one of which is hydrophilic and one hydrophobic, and you heat it up, they separate out into different phases.”

Understanding the role of these underlying physical factors -- dehydration and phase separation -- could enable scientists to engineer improved plants and pretreatment processes and ultimately bring down the costs of biofuel production.

“Our insight is that we have to find a balance which avoids cellulose dehydration but allows phase separation,” Langan said. “We know now what we have to achieve -- we don’t yet know how that could be done, but we’ve provided clear and specific information to help us get there.”

The research is published as “Common processes drive the thermochemical pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass,” and is available online here:http://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2013/gc/c3gc41962b#!divAbstract.

The study’s coauthors are Paul Langan, Loukas Petridis, Hugh O’Neill, Sai Venkatesh Pingali, Marcus Foston, Yoshiharu Nishiyama, Roland Schulz, Benjamin Lindner, B. Leif Hanson, Shane Harton, William Heller, Volker Urban, Barbara Evans, S. Gnanakaran, Jeremy Smith, Brian Davison and Arthur Ragauskas.

The research was funded by DOE’s Office of Science. The study used the resources of ORNL’s High Flux Isotope Reactor (http://neutrons.ornl.gov/facilities/HFIR/) and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory’s National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (http://www.nersc.gov), both of which are user facilities also supported by DOE’s Office of Science.