ENTERTAINMENT

Computer scientist cracks mysterious 'Copiale Cipher'

Translation expert turning insights and supercomputing power on other coded messages

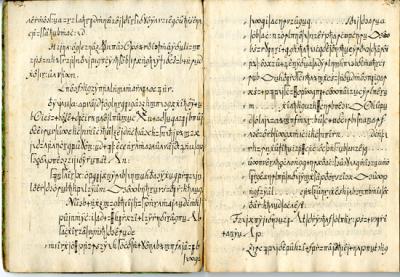

The manuscript seems straight out of fiction: a strange handwritten message in abstract symbols and Roman letters meticulously covering 105 yellowing pages, hidden in the depths of an academic archive.

Now, more than three centuries after it was devised, the 75,000-character "Copiale Cipher" has finally been broken.

The mysterious cryptogram, bound in gold and green brocade paper, reveals the rituals and political leanings of a 18th-century secret society in Germany. The rituals detailed in the document indicate the secret society had a fascination with eye surgery and ophthalmology, though it seems members of the secret society were not themselves eye doctors.

"This opens up a window for people who study the history of ideas and the history of secret societies," said computer scientist Kevin Knight of the USC Viterbi School of Engineering, part of the international team that finally cracked the Copiale Cipher. "Historians believe that secret societies have had a role in revolutions, but all that is yet to be worked out, and a big part of the reason is because so many documents are enciphered."

To break the Copiale Cipher, Knight and colleagues Beáta Megyesi and Christiane Schaefer of Uppsala University in Sweden tracked down the original manuscript, which was found in the East Berlin Academy after the Cold War and is now in a private collection. They then transcribed a machine-readable version of the text, using a computer program created by Knight to help quantify the co-occurrences of certain symbols and other patterns.

"When you get a new code and look at it, the possibilities are nearly infinite," Knight said. "Once you come up with a hypothesis based on your intuition as a human, you can turn over a lot of grunt work to the computer."

With the Copiale Cipher, the codebreaking team began not even knowing the language of the encrypted document. But they had a hunch about the Roman and Greek characters distributed throughout the manuscript, so they isolated these from the abstract symbols and attacked it as the true code.

"It took quite a long time and resulted in complete failure," Knight says.

After trying 80 languages, the cryptography team realized the Roman characters were "nulls," intended to mislead to reader. It was the abstract symbols that held the message.

The team then tested the hypothesis that abstract symbols with similar shapes represented the same letter, or groups of letters. Eventually, the first meaningful words of German emerged: "Ceremonies of Initiation," followed by "Secret Section."

For more information about the method of decipherment, visit http://stp.lingfil.uu.se/%7Ebea/copiale/

Knight is now targeting other coded messages, including ciphers sent by the Zodiac Killer, a serial murderer who sent taunting messages to the press and has never been caught. Knight is also applying his computer-assisted codebreaking software to other famous unsolved codes such as the last section of "Kryptos," an encrypted message carved into a granite sculpture on the grounds of CIA headquarters, and the Voynich Manuscript, a medieval document that has baffled professional cryptographers for decades.

But for Knight, the trickiest language puzzle of all is still everyday speech. A senior research scientist in the Intelligent Systems Division of the USC Information Sciences Institute, Knight is one of the world's leading experts on machine translation -- teaching computers to turn Chinese into English or Arabic into Korean. "Translation remains a tough challenge for artificial intelligence," said Knight, whose translation software has been adopted by companies such as Apple and Intel.

With researcher Sujith Ravi, who received a PhD in computer science from USC in 2011, Knight has been approaching translation as a cryptographic problem, which could not only improve human language translation but could also be useful in translating languages that are not currently spoken by humans, including ancient languages and animal communication.