GOVERNMENT

Dutch supercomputer simulations show how wind farms benefit from strong 'low-level jets' in atmosphere

The height of the latest generation of wind turbines gives rise to effects that are unforeseen. The effects, in terms of performance, are positive in most cases: at these heights, powerful airflows in the lower atmosphere start playing a role and will enable a wind farm to harvest extra energy. University of Twente researchers present their work on this, in the Journal of Renewable and Sustainable Energy.

Strong airflows in the lower atmosphere, so-called ‘low-level jets’, have an impact on the performance of wind farms. The height at which this jet moves, makes the difference: does it flow above the turbines, at the level of the turbines, or even below? This determines if all turbines benefit from it, or just the front row, researchers of the University of Twente demonstrate in their paper in the Journal of Renewable and Sustainable Energy.

Wind turbines, making up a growing share of our ‘energy mix’, have increased in height over the years: the early generations had heights of 50 meter and below, the latest generation exceeds heights of 250 meter, with rotor blades of over 100 meter in length. Effects that are seen in boundary layers in the lower atmosphere, typically at heights between 50 and 1000 meters, start playing an important role. For smaller wind turbines, these effects typically take place above the wind turbine, while for the current sizes, they can play a role at the level of the turbine or even below that. The ‘rivers of air’, called low-level jets (LLJ’s), were observed at many places in the world including the North Sea region.

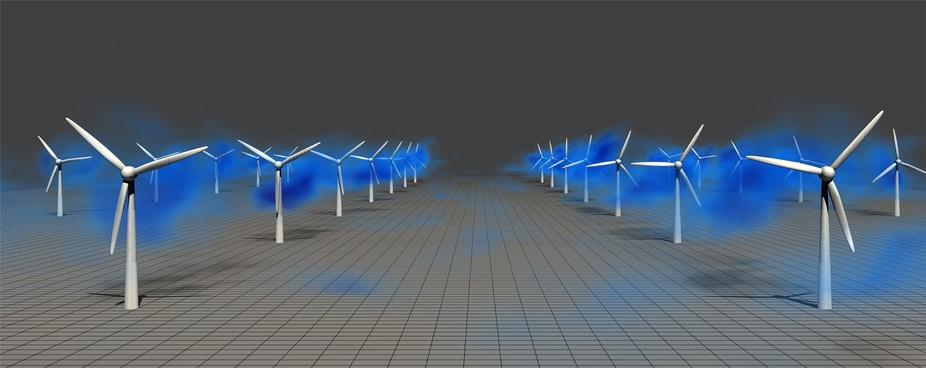

Researchers Srinidhi Gadde and Richard Stevens did extensive supercomputer simulations on a wind farm consisting of 40 turbines, four by ten, to study the effect of LLJ’s on performance. Earlier research showed that the wake of each turbine influences the next turbine in the row. This wake also plays an unexpected role in attracting the low-level jet.

In case the jet flows in the direction of the wind farm, at the level of the wind turbines, it is just the first row of turbines that benefits from it: it has no effect on the turbines further downstream. If the jet is above the wind turbines, however, the turbulent flow behind each turbine causes the jet to move down. Extra energy is harvested by the wind farm as a whole. The most remarkable effect takes place at jets flowing below turbine level: these jets are pushed upward by an effect called negative wind shear, resulting in higher levels of energy for turbines further downstream.

These new insights can help to design the wind turbines and to position them in a wind farm. Further research will have to shed light on effects like the transition from land to sea and several temperature effects.

The research was done in the Physics of Fluids group of the University of Twente. It is part of the Computational Sciences for Energy Research program of Dutch Research Council NWO and Shell.

The paper ‘Effect of low-level jets height on windfarm production’, by Srinidhi Gadde and Richard Stevens, is in the latest edition of the Journal of Renewable and Sustainable Energy (JRSE).