The single-cell organism known as slime mold (Physarum polycephalum) builds complex web-like filamentary networks in search of food, always finding near-optimal pathways to connect different locations.

In shaping the Universe, gravity builds a vast cobweb-like structure of filaments tying galaxies and clusters of galaxies together along invisible bridges of gas and dark matter hundreds of millions of light-years long. There is an uncanny resemblance between the two networks, one crafted by biological evolution, the other by the primordial force of gravity.

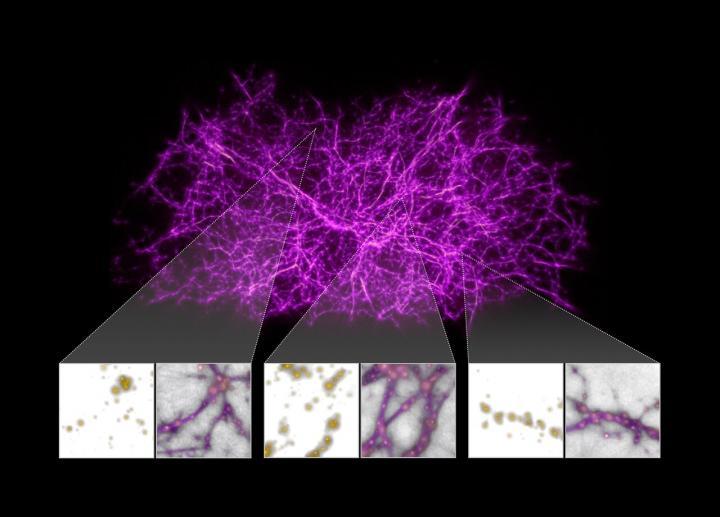

The cosmic web is the large-scale backbone of the cosmos, consisting primarily of dark matter and laced with gas, upon which galaxies are built. Even though dark matter cannot be seen, it makes up the bulk of the Universe's material. Astronomers have had a difficult time finding these elusive strands because the gas within them is too dim to be detected.

The existence of a web-like structure to the Universe was first hinted at in galaxy surveys in the 1980s. Since those studies, the grand scale of this filamentary structure has been revealed by subsequent sky surveys. The filaments form the boundaries between large voids in the Universe. Now a team of researchers has turned to slime mold to help them build a map of the filaments in the local Universe (within 100 million light-years of Earth) and find the gas within them.

They designed a supercomputer algorithm, inspired by the behavior of slime mold, and tested it against a supercomputer simulation of the growth of dark matter filaments in the Universe. A computer algorithm is essentially a recipe that tells a computer precisely what steps to take to solve a problem.

The researchers then applied the slime mold algorithm to data containing the locations of over 37 000 galaxies mapped by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. The algorithm produced a three-dimensional map of the underlying cosmic web structure.

They then analyzed the light from 350 faraway quasars cataloged in the Hubble Spectroscopic Legacy Archive. These distant cosmic flashlights are the brilliant black-hole-powered cores of active galaxies, whose light shines across space and through the foreground cosmic web. Imprinted on that light was the telltale signature of otherwise invisible hydrogen gas that the team analyzed at specific points along the filaments. These target locations are far from the galaxies, which allowed the research team to link the gas to the Universe's large-scale structure.

"It's really fascinating that one of the simplest forms of life actually enables insights into the very largest-scale structures in the Universe," said lead researcher Joseph Burchett of the University of California (UC), U.S.A. "By using the slime mold simulation to find the location of the cosmic web filaments, including those far from galaxies, we could then use the Hubble Space Telescope's archival data to detect and determine the density of the cool gas on the very outskirts of those invisible filaments. Scientists have detected signatures of this gas for over half a century, and we have now proven the theoretical expectation that this gas comprises the cosmic web."

The survey further validates research that indicates intergalactic gas is organized into filaments and also reveals how far away gas is detected from the galaxies. Team members were surprised to find gas associated with the cosmic web filaments more than 10 million light-years away from the galaxies.

But that wasn't the only surprise. They also discovered that the ultraviolet signature of the gas gets stronger in the filaments' denser regions, but then disappears. "We think this discovery is telling us about the violent interactions that galaxies have in dense pockets of the intergalactic medium, where the gas becomes too hot to detect," Burchett said.  {module INSIDE STORY}

{module INSIDE STORY}

The researchers turned to slime mold simulations when they were searching for a way to visualize the theorized connection between the cosmic web structure and the cool gas, detected in previous Hubble spectroscopic studies.

Then team member Oskar Elek, a computer scientist at UC Santa Cruz, discovered online the work of Sage Jenson, a Berlin-based media artist. Among Jenson's works were mesmerizing artistic visualizations showing the growth of a slime mold's tentacle-like network of structures moving from one food source to another. Jenson's art was based on scientific work from 2010 by Jeff Jones of the University of the West of England in Bristol, which detailed an algorithm for simulating the growth of slime mold.

The research team was inspired by how the slime mold builds complex filaments to capture new food, and how this mapping could be applied to how gravity shapes the Universe, as the cosmic web constructs the strands between galaxies and galaxy clusters. Based on the simulation outlined in Jones's paper, Elek developed a three-dimensional supercomputer model of the buildup of slime mold to estimate the location of the cosmic web's filamentary structure.

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?